Injury, Stress, and Perfectionism in Young Dancers and Gymnasts

Donna Krasnow, M.S., Lynda Mainwaring, Ph.D., C.Psych., and Gretchen Kerr, Ph.D.

Journal of Dance Medicine & Science • Volume 3, Number 2, 1999.

Abstract

Injuries, psychological stress, and perfectionism were examined in three groups of young elite performers: ballet dancers, modern dancers, and artistic gymnasts. Similar to the adult population, a high incidence of injury was found for all three groups. Results revealed a greater number of hip injuries in young ballet dancers and gymnasts than typically found in the adult population. Variations were found among the groups in injury management, and duration of time training was modified. Relationships between injury and stress, and injury and perfectionism were not uniform across groups. The study points to the importance of distinguishing between positive and negative stressors in role specific activities. The complexities of the stress/injury phenomenon and the multifaceted nature of the perfectionism variable were identified. The authors emphasize the need for further research and education in the area of youth injuries and psychological correlates in order to minimize the negative effects on young elite performers.

Injuries can have profound negative consequences on the health and performance of young dancers and gymnasts. Performance and training demands on these two groups are often substantial in the teen years and leave them vulnerable to injury. Typically, dancers endure overuse injuries[1-3] whereas gymnasts tend to suffer slightly more traumatic injuries.[4-7] Although it is difficult to compare injury incidence across groups and studies because of the differences in injury reporting and definition, it is clear that the young elite female dancer and gymnast are at high risk for injury. For example, injury rates per 100 participant seasons range from 12.[88] to 1,375.[79] for young gymnasts. For young dancers, incidence of injury has been reported to be as high as 161.[52] and 33610 per 100 participant seasons.

Adolescent ballet dancers may be at an increased risk for injuries, such as stress fractures,[11] compared with adolescent non-dancers, modern dancers, and older dancers.[12] In non-dancers, the female skeleton is growing the fastest at age 11.7 years,[13] and is therefore less dense, more fragile, and vulnerable because of thinning cortical bone.[14] Injuries reported in young ballet dancers include, anterior knee pain syndrome, medial tibial stress syndrome,[10] tendinitis, fractures or stress fractures,[15] scoliosis, [11] and ankle injuries.[16] In general, in all age groups and dance forms, lower leg injuries (typically of the knee) account for the greatest prevalence of injuries. However, there is evidence to suggest that adolescent female dancers incur unique or different injuries than are found in the adult population,[16,17] and that lower back injuries are more prevalent in adult modern dancers.[17,18] The need to identify differences in injury patterns, particularly as they relate to young dancers and athletes, has been acknowledged.[17] The present study examined the nature of injuries in young dancers and gymnasts.

In addition to identifying patterns of injury in those groups, the study explored stress and perfectionism as possible psychological correlates of injury. The most commonly accepted definition of stress refers to a relationship between a person and the environment that is appraised as taxing personal resources and threatening well-being.[19] This definition is valuable as it accounts for individual differences and the importance of appraisal; one person may appraise or evaluate a specific situation as stressful, another may not. Stress is typically assessed through stressful life events, or life stressor, checklists. These measures include positive events such as personal accomplishments and negative events such as loss of a loved one. The basic premise of this area of research is that life stressors involve a change in lifestyle that requires adaptation or adjustment, which in turn requires energy. [20] An event becomes stressful when an individual appraises the demands of the change as exceeding his or her capacity to cope with it effectively. It is believed that the accumulation of life stressors taxes an individual’s coping resources, thus increasing his or her susceptibility to fatigue, illness, or injury. [21,22] When examining life stress, it is critical to include both major life events that are common to the general population as well as those day-to-day stressors that we encounter in our particular roles. For athletes or dancers therefore, an investigation of stress should include general stressors, such as illness of a loved one, in addition to daily athletic or dance-specific stressors such as interpersonal difficulties with instructors or time demands between school and training.

Prior research has demonstrated significant relationships between psychological stress and illness as well as stress and injury in sport[22-29] and dance.[30-32] Increased stress has been associated with the number and severity of injured dancers[31,33] as well as with amount of time dancers were injured.[31] Leiderbach and colleagues[32] found that injury trends for young adult professional dancers seemed to be related to timespecific onset of performance-related psychological and physiological stress. Not only is psychological stress linked to injury and illness, but evidence suggests that the personality construct of perfectionism is linked to both physiological and psychological disorders including coronary heart disease,[34] anorexia nervosa, depression, dysmorphophobia, and ulcerative colitis.[35]

Current research indicates that perfectionism is a multidimensional construct that is instrumental in a variety of psychopathologies and adjustment problems.[36-39] In the past, a precise definition and an established measure of perfectionism was not available. Recently, Frost and associates[39] defined perfectionism as the setting of excessively high standards of performance in conjunction with a tendency to make overly critical self-evaluations; and these researchers developed the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS). The scale provides an overall perfectionism score from five primary dimensions: Personal Standards, Concern over Mistakes, Parental Expectations, Parental Criticism, and Doubts about Actions. Concern over Mistakes is correlated with a wide range of psychopathology, frequency of procrastination, and general distress, whereas, Personal Standards is associated with positive achievement. The Parental Expectations scale measures the perception that parents have high expectations and the extent to which parents are perceived as overly critical is measured by Parental Criticism. Doubts about Actions “captures a vague sense of doubt about the quality and success of one’s performance.”[40]

A common theme in perfectionism theory is that perfectionists are motivated by a fear of failure, and thus, any evaluated performance is viewed as an opportunity to fail rather than to succeed. [41] It has been suggested that perfectionistic athletes fear failure and mistakes to the extent that enjoyment of sport is greatly diminished and performance is impeded.[42-44] An integral aspect of the perfectionism construct is performance standards, which is a primary focus in elite dance and sport. Therefore, examining the role perfectionism plays in elite performance seems a worthy pursuit for which little empirical research exists.

Frost and Henderson[40] investigated perfectionism (as well as certain dimensions of that construct) and reactions to athletic competition among female athletes. Overall, athletes who scored high in Concern over Mistakes reported more anxiety and less self-confidence (in the athletic context), displayed a general failure orientation toward sports, reacted negatively to mistakes, and reported more negative thinking in the 24 hours prior to competition.[40] Those athletes had a difficult time forgetting about their mistakes and reported that images of their mistakes controlled their mind during the remainder of the competition. These findings, the need for injury data in young populations, and research that shows that poor attention as well as increased stress may lead to injury,[45] provided the impetus for the present study.

The study examines injury, stress, and perfectionism in adolescent dancers and gymnasts by comparing these variables in modern and ballet dancers and artistic gymnasts. We hypothesized that positive relationships would exist between injuries and psychological stress, injuries and perfectionism, and psychological stress and perfectionism. Also, we anticipated that ballet dancers and gymnasts would report more injuries as well as higher levels of stress and perfectionism than modern dancers.

Materials and Method

Participants

The participants in the study included 30 artistic gymnasts, 19 modern dancers, and 16 ballet dancers. All participants were female, Canadian, between the ages of 12 and 18 years of age (mean: 15.5 ± 0.5), and attended school on a full-time basis. Most of the participants began their dance or gymnastics training before the age of 6 and had been training for 10 or more years. At the time of the assessment, most trained five or more times per week and had significant experience with performance or competition.

Measures

Dance/Gymnastics Questionnaire[46]

The survey was designed for the purpose of this study to obtain background information on the participants, their personal history in dance or gymnastics, their injury history, and the treatment they sought. The questionnaire consisted of 44 questions and required approximately 20 minutes to complete. Injury, for the purpose of this study, was defined as any physical harm resulting in pain or discomfort that causes one or more of the following:

1. Cessation of dance/gymnastics activity during one or more classes, rehearsals, or performances;

2. A need to modify dance/gymnastics activity during one or more classes, rehearsals, or performances;

3. Negative effects on training or performances during one or more

classes, rehearsals, or performances; 4. Sufficient distraction or emotional distress to interfere with concentration or focus during one or more classes, rehearsals, or performances.

Injury was defined in this way as many injuries do not cause dancers and gymnasts to refrain totally from practice.

Dance Experience Survey[30]

This measure was designed to assess stressors that are unique to dancers (rolespecific stressors). It was modelled after the Life Experience Survey.[47] The survey includes 48 stressors such as “relationships with teachers,” “relationships with choreographers,” and “politics associated with dance activities.” The dancers were asked to rate each applicable stressor on an impact scale ranging from -3 (extremely negative) to +3 (extremely positive), which allowed for the distinction between positive and negative stressors. For example, “relationship with choreographer” may be rated as +2 if the relationship is fairly positive, enjoyable, and productive, or as -2 if the relationship is characterized by moderate conflict or distress. Blank spaces were provided for participants to report any stressors not included in the list. Approximately 8 minutes were required to complete the survey.

Gymnastics Experience Survey[48]

Similar to the Dance Experience Survey, this measure was designed to assess those stressors that are unique to athletes in the role of gymnastics. Again, it was designed after the Life Experiences Survey.[48] Consisting of 48 items such as “relationship with coach” and “weight control,” this measure required approximately 8 minutes to complete. Each stressor is rated on a scale from -3 (extremely negative) to +3 (extremely positive), thus allowing for the distinction between positive and negative stress. Again, blank spaces were provided for participants to report any stressors not included in the list.

Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale[39]

The multidimensional Perfectionism Scale contains 47 items that fit conceptually into each of five dimension of perfectionism: Personal Standards, Concern over Mistakes, Parental Expectation, Doubts about Actions, and Parental Criticism. All items are presented in the form of statements with a five point Likert-response scale continuum ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The coefficients of internal consistency ranged from 0.77 to 0.93 with a reliability of the total perfectionism scale of 0.90. This measure correlates positively with the Burns’ Perfectionism Scale[49] and the Perfectionism Scale from the Eating Disorder Inventory.[50]

Results

Injury Data

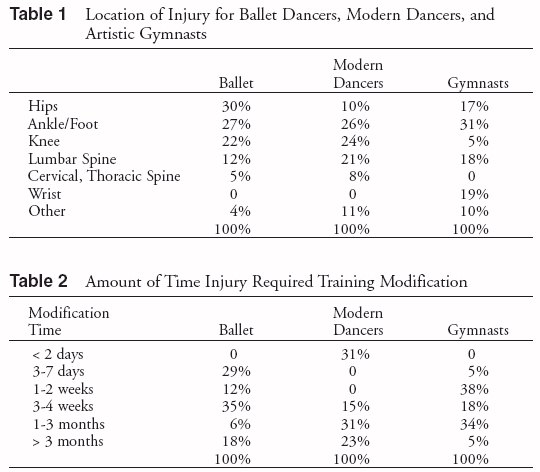

The results indicated that 100% of the gymnasts had experienced at least one injury during their career. For dancers, 94% of those who studied ballet experienced at least one injury, and 79% of those who studied modern reported at least one injury. The sites of these injuries are shown in Table 1.

The participants were asked to report the amount of time that training needed to be modified for each injury. The duration of these injuries in each group are shown in Table 2. Participants were also asked to identify the type of treatment sought for their injuries. Of the ballet dancers, 58% sought treatment from physical therapists and 19% consulted physicians. The modern dancers showed more variety in their selection of treatment with 22% seeking the assistance of dance teachers and 22% consulting chiropractors. Medical doctors and physical therapists each were seen by 19% of the modern dancers. Furthermore, approximately half of the modern dancers sought the assistance of more than one type of practitioner. The gymnasts relied exclusively on medical doctors (60%), physical therapists (20%), and chiropractors (20%) for the treatment of their injuries.

Stress Data

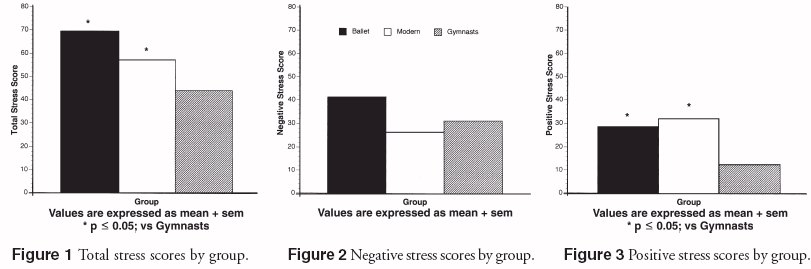

The results for total stress scores (combined positive and negative stress), negative, and positive stress scores are shown in Figures 1, 2, and 3 respectively. A oneway ANOVA indicated significant between group differences (F = 7.99; df = 2,62; p < 0.008). A Fisher post-hoc test revealed that the ballet and modern dancers reported significantly more total stress than the gymnasts. Although not statistically significant, a trend existed with ballet dancers who reported more negative stress than modern dancers (F = 2.69; df = 2,62; p < 0.076). With respect to positive stress, a oneway ANOVA indicated significant between group differences (F = 13.40; df=2,62; p < 0.0001). A Fisher post-hoc test revealed that the ballet and modern dancers reported significantly more positive stress than did the gymnasts.

Perfectionism

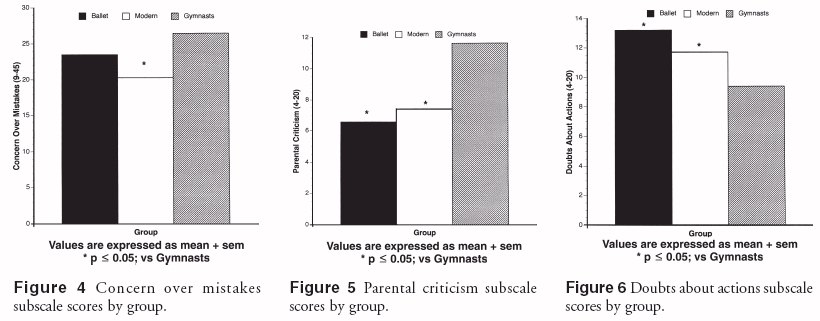

One-way ANOVAs indicated that between group differences existed with respect to the three perfectionism subscales, Concern over Mistakes, Parental Criticism, and Doubts about Actions. More specifically, Fisher post-hoc tests revealed that modern dancers reported significantly less Concern over Mistakes than did gymnasts (F = 3.33; df = 2,62; p < 0.04). The ballet dancers did not significantly differ in Concern over Mistakes from the gymnasts or the modern dancers (Fig. 4).

A Fisher post-hoc test indicated that both the ballet and modern dancers reported significantly less Parental Criticism than did the gymnasts (F = 15.78; df = 2,62; p < 0.0001). The ballet and modern dancers, however, did not significantly differ from each other (Fig. 5). Between group differences also emerged on the Doubts about Actions sub-scale with the gymnasts reporting significantly less doubts than either the ballet or modern dancers (F = 10.80; df = 2,62; p < 0.0001). Again, the ballet and modern dancers did not differ significantly from each other (Fig. 6).

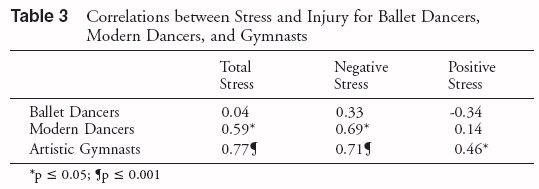

Relationships between Stress and Injury

Pearson Product Moment Correlations between the stress and injury data are shown in Table 3. The results indicated that for the ballet dancers there were no significant relationships between any of the stress scales and injury. In contrast, for the modern dancers significant positive correlations existed between injury and both total stress and negative stress. Gymnastic injuries were correlated in a positive direction with total, positive, and negative stress.

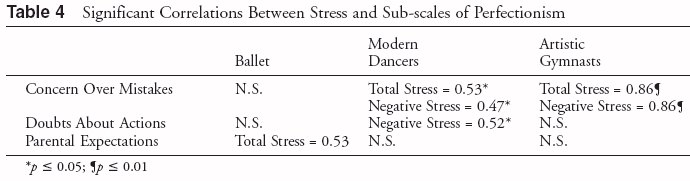

Relationships between Stress and Perfectionism

Pearson Product Moment Correlations were conducted between the stress scales (total stress, positive stress, and negative stress) and the six subscales of perfectionism. Table 4 illustrates those correlations that reached statistical significance. Total stress and negative stress were correlated with Concern over Mistakes for both modern dancers and artistic gymnasts. Doubts about Actions was correlated only with negative stress for modern dancers. Finally, total stress and Parental Expectations were positively correlated for ballet dancers only. No significant correlations were found between stress and the other three subscales of perfectionism (Personal Standards, Parental Criticism, and Organization).

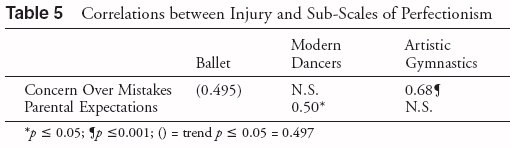

Relationships between Injury and Perfectionism

As shown in Table 5, a significant positive correlation resulted between number of injuries and the sub-scale of Parental Expectations for modern dancers. The Concern over Mistakes sub-scale was correlated significantly with injury for artistic gymnasts and a trend resulted between these two variables for ballet dancers. No significant relationships were found between injury and the other sub-scales of perfectionism.

Discussion

Injury

Although a broad definition of injury was used in this study, the high number of injuries to young dancers and gymnasts echo the incidence of injury in older dance populations. However, findings reveal a greater number of hip problems in young ballet dancers (and gymnasts to some extent) than in older dancers in whom lower leg, foot, and ankle problems are more prevalent (see Table 1). Perhaps the extreme range of motion demanded in ballet and gymnastics is problematic during adolescence, especially during the growth spurts. Current literature reports that external rotation of the hip is very limited prior to age 12, but increases with age.[51] Garrick[16] found that hip injuries were seen more commonly in 13 to 38-yearold dancers, and snapping hip syndrome has been associated with a narrow bi-iliac width.[52] Molnar and Esterson[15] reported that it is “imperative to take into account bone growth, hormonal status, growth spurts, and nutrition,” when working with young dancers whose bodies are subjected to great physical demands while training. They found their sample of young ballet students to be globally weak in trunk strength and questioned whether there is a correlation between trunk strength and anterior hip tightness. Similarly, our findings lead us to question the relationship between trunk strength, hip tightness, and injury, and to suggest that more careful strength training for the trunk support muscles, and hip joint muscles in adolescent elite ballet dancers and gymnasts is needed. Also, the high incidence of reported lumbar spine problems in the modern dancers suggests that additional trunk strength may be needed in this group also.

We were prohibited from asking questions about menstrual function and eating patterns by the consenting adults for one of the three groups in our study. Hence it was not possible to examine the relationship between injury and eating disorders.

Differences in injury management were evident among the groups. Precise medical information on the injuries was not available, so the nature and severity of injuries among the groups may have been quite different. Also, the self-reports of injury were lacking adequate descriptions. It is clear from this research and that of Molnar and Esterson[15] that dancers need better education about injury management. Young dancers and gymnasts knew very little about what structures were injured and the mechanism of injury. It is to their advantage to have greater knowledge of the structure and function of their bodies as well as the nature and process of injury and recovery. The varied injury management strategies may have been based on lack of knowledge, availability of practitioners, or attitudes toward treatment. The data shows that modern dancers had the least contact with physicians and physical therapists, and that they sought treatment from a greater range of sources: the ballet dancers and gymnasts in the study were more likely to visit physicians or physical therapists than were the modern dancers. Prior research[53] noted that modern dancers reported a lack of access to physicians and physical therapists, or an unwillingness to seek their assistance.

The majority of participants in our sample modified training for longer than three weeks due to injury (59% of ballet dancers, 69% of modern dancers, and 57 % of gymnasts). However, while the ballet and gymnastic groups typically modified activity for three days to three months, the modern dancers either modified activity for a very short time (less than two days) or for one month or longer (54%). Only 24% of the ballet group and 39% of the gymnasts modified activity for one or more months. From a review of the literature, Caine and Garrick[17] inferred that 28.8% to 35.6% of dancers incurred injuries that kept them from training for more than one week. Those authors also concluded that tendinitis about the hip resulted in the longest absence from training (6.9 days) followed by low back strain (4.7 days). Hamilton and colleagues[54] found that the average length of disability for a sample of students from the School of American Ballet was 54 days. Eight (5%) students dropped out of the school because they had missed over four months. In our study, the average amount of time lost to injury for ballet students was three to four weeks, whereas 18% of the ballet students modified activity for greater than three months but none dropped-out of dancing.

In summary, our data suggests that there are differences among dancers and gymnasts in the management of, and disability from, injury. Training is typically affected for between one week and one month for ballet dancers and gymnasts, whereas modern dancers modify training for much less or much longer periods. It could be that the modern dancers in the study returned to activity too soon. Nevertheless, it appears that, in general, large numbers of young elite participants are modifying training for weeks, rather than days, and appropriate monitoring of training, technique, and injury management is needed.

Psychological Stress

In terms of psychological stress, the results point to the importance of discerning among positive, negative, and total stress. Each may be associated differently with injury and personality as revealed in the present and prior[31] research. Total stress may mask differences in stressors. For example, the ballet and modern dancers both had higher total stress levels than the gymnasts, but the gymnasts had lower levels of positive stress. Positive stress, or eustress, is an essential stimulus for psychological growth, creativity, and life satisfaction, and may buffer the negative stressors that occur.

There are certain contextual factors that may contribute to the low levels of positive stress reported by the gymnasts. First, gymnasts generally do not have access to stress management or psychological support programs; in fact, in many cases gymnasts have been prohibited from accessing these resources. Furthermore, prior research has found that gymnasts have a very singular identity, such that their lives and identities revolve around gymnastics. And finally, gymnasts’ lives, both within and outside the training environment, tend to be very regimented and controlled, leaving these athletes with little autonomy and leisure time.

Correlations between total stress and injury and between negative stress and injury were both significant for the gymnast and modern groups. These correlations were especially high for the gymnasts whereas no such relationship was revealed for the ballet group, as we had hypothesized. The high positive stress, or some additional factor, may have moderated the training or lifestyles of the ballet students and accounted for this result. The ballet students lived at the school with a more controlled environment, which may have provided an enhanced support system. It is well documented that social support buffers stress,[55,56] and may have moderated the effects of negative stress on injury in this study. Hamilton and associates[54] advocated that dance students be provided programs to alleviate occupational stress due to the difficulties with injuries and disordered eating found in their study.

Perfectionism

Differences in perfectionism subscales (rather than total perfectionism scores as hypothesized) and their association with injury and stress were found among the three groups. Modern dancers were less concerned over mistakes than gymnasts, and both groups of dancers had higher scores on the Doubt about Actions scale. Gymnasts, however, were more concerned about parental criticism. We question whether these differences are an artifact of the artistic nature of ballet and modern dance, and insecurities that might arise in studying these two forms. Gymnasts have a more precise and concrete standard for achievement than do dancers. It is difficult to determine if these differences are related to the nature and varying demands of the three forms or if they indicate something about differences in personality.

The ballet dancers differed from the other two groups with respect to the relationship between perfectionism and stress. Parental Expectations correlated significantly with total stress for ballet dancers. Concern over Mistakes was associated with both total and negative stress for gymnasts and modern dancers. Again, it may be that environmental or personality differences account for these results. Further investigation is needed to understand the distinctions.

In terms of injury and perfectionism, the hypothesis that there would be a positive relationship was not supported, but again, like injury and stress, the picture was much more complex. The relationships between injury and the various subscales of perfectionism varied among the groups with modern dancers showing a different pattern than the other two groups. Only the Parental Expectations subscale was shown to be related significantly with injury for modern dancers. Injury and Concern over Mistakes were correlated significantly for the gymnasts, and a strong trend was found between these two variables for the ballet group. Previous research[31] found that physical stress and personality traits characteristic of the “overachiever” distinguished injured ballet dancers from the normal population. The authors of that study reported that dancers with a greater number of injuries were more enterprising, and dancers with stress fractures were also more dominant, extroverted, assertive, sociable, and adjusted. In addition to exploring the role that personality plays in the attraction adolescents have for the various forms, we need to investigate how training methods and significant others are affecting young dancers and athletes.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The findings of this study indicate that injuries are high in young dancers and gymnasts. Hip injuries were particularly prevalent in these groups. More research is needed to explore and confirm this result as well as to examine training and conditioning of the trunk and hip joint muscles during the growth years. In addition, we need to investigate if young modern dancers are receiving adequate treatment for their injuries, why they do not seek assistance from physicians and physical therapists, and whether they are taking sufficient time away from training during the early stages of injury. It is clear that the majority of professional dancers pursue elite training at between 12 to 18 years of age, and information on this age group is crucial in terms of its long-term impact on the young dancers and the art form. Similarly, gymnasts start demanding training schedules very early in life, and the high number of injuries found in this study caution scientists and coaches to examine these demands more carefully.

It is noteworthy that gymnasts have fairly high levels of stress but have reduced positive stress when compared with the two dance groups. In earlier research[30] the duration of injury was considerably shorter when associated with positive stress as opposed to negative stress. Researchers need to continue looking at all types of stressors and their relationship to dance/athletic injuries. Also, it would be helpful to examine conditions that contribute to greater stress for dancers and elevated negative stress for gymnasts.

More research on larger samples of the population is needed on the psychological correlates of injury in order to determine if injuries can be reduced not only through enhancing physical training, but also by enhancing the psychological care of young dancers and athletes. We need to explore whether training methods are encouraging a high concern over mistakes; that subscale of perfectionism was found to be related strongly to injury for ballet dancers and gymnasts and with high stress (total positive and negative) for modern dancers. It would also be beneficial to explore the environment, personality, coping resources, and social support as possible mediating variables in the stress/injury relationship. In addition, we believe that the relationships between elite dancers and gymnasts and their teachers is extremely influential and needs to be explored. Only parents’ expectations and criticism are measured in Frost’s perfectionism measure, and we have seen that perfectionism needs to be addressed from a multifaceted perspective, especially with elite performers. Therefore, we are in the process of designing a scale that addresses significant others’ expectations and will include coaches’/teachers’ influences. Additionally, normal values for the level of perfectionism need to be established for comparison.

Finally, there is no question that elite training for the young will promote high standards, result in physical and psychological stress, and incur injury. Contemporary research points to the multifactorial causes and consequences of performance injuries and the importance of examining both physical and psychological factors in their prevention and treatment.[57] Researchers and educators need more information about correlates of injury, such as stress and perfectionism, and how training might be modified to reduce the impact of these factors on the incidence of injury. Perhaps training should be reduced or modified during high stress times, such as exams. The way that we train elite dancers and athletes may be encouraging an over-emphasis on “concern for mistakes,” and this should be examined. We also need to consider if the demand for perfection that comes from teachers and coaches contributes to injury patterns and adverse psychological health of these young people. Further research and enhanced knowledge can assist educators, trainers, and the participants themselves in creating optimal training methods and minimizing negative effects of elite performance in the young artist and athlete.

References

1. Quirk R: Ballet injuries: The Australian experience. Clin Sports Med 2:507-514, 1983.

2. Rovere GD, Ebb LX, Gristina AG, Vogel JM: Musculoskeletal injuries in theatrical dance students. Am J Sports Med 11:195-199, 1983.

3. Washington EL: Musculoskeletal injuries in theatrical dancers: Site, frequency, and severity. Am J Sports Med 6:75-98, 1978.

4. Garrick JG, Requa RK: Epidemiology of women’ gymnastics injuries. Am J Sports Med 8:261-264, 1980.

5. Pettrone FA, Ricciardelli E: Gymnastic injuries: The Virginia experience, 1982-1983. Am J Sports Med 15:59- 62, 1987.

6. Snook GA: Injuries in women’s gymnastics. Am J Sports Med 7:242-244, 1979.

7. Weiker CG: Injuries in club gymnastics. Phys Sportsmed 13:63-66, 1985.

8. Goodway JD, McNaught-Davis JP, White J: The distribution of injuries among young female gymnasts in relation to selected training and environmental factors. In: Beunen G (ed): Children and Exercise. Stuttgart: Enke Verlag, 1989.

9. Sands WA, Shultz BB, Newman AP: Women’s gymnastics injuries: A 5-year study. Am J Sports Med 21(2):271- 276, 1993.

10. Reid D: Preventing injuries to the young ballet dancer. Physiotherapy Canada 39(4):231-236, 1987.

11. Hamilton L, Hamilton W, Warren M: Injury prevention in ballet: Physical, nutritional, and psychological considerations. Presented at the Annual APA Convention, Toronto, 1993.

12. Schafle M, Requa R, Garrick J: A comparison of patterns of injury in ballet, modern, and aerobic dance. In: Solomon R, Minton S, Solomon J (eds): Preventing Dance Injuries: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Reston, VA: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 1990, pp. 1-14.

13. Grimston S, Nigg BM, Hanley DA, Ensberg JR: Differences in ankle joint complex range of motion as a function of age. Foot Ankle 14 (4):215- 222, 1993.

14. Parfitt AM: The two faces of growth: Benefits and risks to bone integrity. Osteoporosis Int 4:382-398, 1994.

15. Molnar M, Esterson J: Screening students in a pre-professional ballet school. J Dance Med Sci 1(3):118- 121, 1997.

16. Garrick J: Age and injury in ballet. In: WA Grana (ed): Advances in Sports Medicine and Fitness. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers, 1988.

17. Caine C, Garrick J: Dance. In: Cain DJ, Caine CG, Lindner KJ (eds): Epidemiology of Sport Injuries. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers. 1996, pp. 124-160.

18. Kerr G, Krasnow D, Mainwaring L: The nature of dance injuries. Med Probl Perform Art 7:25-29,1992.

19. Lazarus R, Folkman S: Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer Verlag, 1984.

20. Holmes T, Rahe R: The social readjustment rating scale. J Psychosom Res 11:213-218, 1967.

21. Rabkin J, Struening E: Life events, stress and illness. Science 194:1013- 1020, 1976.

22. Smith R, Smoll F, Ptacek J: Conjunctive moderator variables in vulnerability and resiliency: Life stress, social support and coping skills, and adolescent sport injuries. J Pers Soc Psych 58:360-370, 1990.

23. May J, Sieb G: Athletic injuries: Psychosocial factors in the onset, sequelae, rehabilitation and prevention. In: May JR, Asken MJ (eds): Sport Psychology: The Psychological Health of the Athlete. New York: PMA Publishing, 1987, pp. 157-185.

24. Williams J, Roepke N: Psychology of injury and injury rehabilitation. In: Singer R, Murphey M, Tennant LK (eds): Handbook of Research on Sport Psychology. New York: MacMillan, 1993, pp. 815-839.

25. Bramwell S, Masuda M, Wagner N, Holmes T: Psychosocial factors in athletic injuries. J Hum Stress 1:6-20, 1975.

26. Cryan P, Alles W: The relationship between stress and college football injuries. J Sports Med 23:52-58, 1983.

27. Passer M, Seese M: Life stress and athletic injuries: Examination of positive versus negative events and three moderator variables. J Hum Stress 9:11-16, 1983.

28. May J, Veach T, Reed M, Griffey M: A psychosocial study of health injury and performance in athletes on the U.S. Alpine ski team. Phys Sportsmed 13:111-115, 1985.

29. May J, Veach T, Southard S, Herring M: The effects of life change on injuries, illness and performance in elite athletes. In: Butts N, Gushiken T, Zerins B (eds): The Elite Athlete. New York: Spectrum, 1985.

30. Mainwaring L, Kerr G, Krasnow D: Psychological correlates of dance injuries. Med Probl Perform Art 8:3-6, 1993.

31. Hamilton LH, Hamilton WG, Meltzer JD, Marshall P, Molnar M: Personality, stress, and injuries in professional ballet dancers. Am J Sports Med 17:263-267, 1989.

32. Liederbach M, Gliem G, Nicholal J: Physiologic and psychological measurements of performance stress and onset of injuries in professional ballet dancers. Med Probl Perform Art 9:10- 14, 1994.

33. Bowling A: Injuries to dancers: Prevalence, treatment, and perceptions of causes. Brit Med J 298:731-734, 1989.

34. Smith TW, Brehm SS: Cognitive correlates of the type A coronary-prone behaviour pattern. Motivation and Emotion 3:215-223, 1981.

35. Pacht A: Reflections on perfection. Amer Psych 39:386-390, 1984.

36. Hewitt PL, Flett GL: Perfectionism and depression: A multidimensional analysis. J Soc Behav Pers 5:423-428, 1990.

37. Hewitt PL, Flett GL: Dimensions of perfectionism in unipolar depression. J Abnorm Psych 100:98-101, 1991.

38. Hewitt PL, Flett GL: Dimensions of perfectionism, daily stress, and depression: A test of the specific vulnerability hypothesis. J Abnorm Psych 102:58-65, 1993.

39. Frost R, Marten R, Lahart C, Rosenblate R: The dimensions of perfectionism. Cog Ther Res 14:449-468, 1990.

40. Frost RO, Henderson KJ: Perfectionism and reactions to athletic competition. J Sport Exer Psych 13:323-335, 1991.

41. Hamachek DE: Psychodynamics of normal and neurotic perfectionism. Psych 15:27-33, 1978.

42. Bunker L, Williams JM: Cognitive techniques for improving performance. In: Williams JM (ed): Applied Sport Psychology. Mountainview, CA: Mayfield, 1986.

43. Burns DD: The perfectionist’s script for self-defeat. Psych Today. November, pp. 34-51, 1980.

44. Gauron EF: Mental Training for Peak Performance. Lansing, NY: Sport Science Associates, 1984.

45. Kerr G, Minden H: Psychological factors related to the occurrence of athletic injuries. J Sport Exerc Psycho 10:167-173, 1988.

46. Krasnow D, Mainwaring L, Kerr G: Dance/gymnastics questionnaire. Unpublished survey. 1996.

47. Sarason I, Johnson J, Siegel J: Assessing the impact of life changes: Development of the Life Experiences Survey. J Consult Clin Psych 46:932-946, 1978.

48. Kerr G: Gymnastics experiences survey. Unpublished Survey, 1989.

49. Burns D: The perfectionist’s script for self-defeat. Psych Today November, pp. 34-51, 1980.

50. Garner D, Olmstead M, Polivy J: Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Int J Eat Dis 2:15-34, 1983.

51. Siev-Ner I, Barakm A, Heim M, Warshvsky M, Azaria M: The value of screening. J Dance Med Sci 1(3):87- 92, 1997.

52. Jacobs M, Young R: Snapping hip phenomenon among dancers. Am Correct Ther J 32(3):92-98, 1978.

53. Krasnow D, Kerr G, Mainwaring L: Psychology of dealing with the injured dancer. Med Probl Perform Art 9:7-9, 1994.

54. Hamilton LH, Hamilton WG, Warren MP, Keller K, Molnar M: Factors contributing to the attrition rate in elite ballet students. J Dance Med Sci 1(4):131-138, 1997.

55. Dunkel-Schetter C, Bennett TL: The availability of social support and its activation in times of stress. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR , Pierce GR (eds): Social Support: Interactional View. New York: John Wiley, 1990.

56. Schwarzer R, Leppin A: Social support and health: A theoretical and empirical overview. J Soc Per Rel 8:99-127, 1991.

57. Solomon R, Minton S, Solomon J: Preventing Dance Injuries: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Reston, VA: American Association for Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 1990.