A Teacher’s Guide to Helping Young Dancers Cope with Psychological Aspects of Hip Injuries

Lynda Mainwaring, Ph.D., C.Psych., Donna Krasnow, M.S., and Lauren Young.

Journal of Dance Education • Volume 3, Number 2, 2003.

Abstract

Hip injuries are a potentially significant and debilitating condition. In addition to the physical complications,there are serious psychological consequences that can be as incapacitating as the physical damage. This review presents two case studies that describe salient issues that may arise when a young dancer is injured, and outlines practical strategies to help teachers manage psychological recovery in class and rehearsal. The two adolescent females in these examples each suffered a long-term, chronic injury to the hip and were subsequently unable to dance for a period of several months.They each discuss the ongoing progress of the injury, and the resultant devastation they experienced emotionally. Practical strategies for helping young dancers cope with the psychological aspects of hip injuries include: modification of dance activities, alternative activities during dance practice,activities outside the studio, and the encouragement of psychosocial strate- gies for recovery. Each of these areas is examined and suggestions are provided for dance teachers dealing with injured dancers.

Hip injuries have been identified as a potentially significant and debilitating condition in the adolescent dancer. [1-3] In addition to the physical damage, there can be negative or distressing psychological consequences. No empirical work exists on the psychological implications of these injuries. Research of the psychological impact of dance injuries, in general, is in its infancy, and follows the lead from theoretical and empirical work in sport psychology.

In the early 1980’s sport scientists suggested that the psychological response to injury was similar to Elizabeth Kübler-Ross’ five-stage theory of grief (Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression and Acceptance). [4-6]

Later in the same decade, researchers began to conduct empirical studies to examine the psychological response to athletic injury. [7-15]

Today in the field of sport psychology, models of psychological response to injury, which do not follow Kübler-Ross’ grief model, are evolving. [9,11,13,16]

These models identify a more dynamic reaction to sport injury than that depicted by five sequential stages. While we can learn about reaction to injury in general from the field of sport psychology,dance educators and scientists need to examine dancers’ responses to injury because of the unique context in which dancers train and work. Moreover, the reactions of adult athletes to injury may be quite different from those of adolescent female dancers.

Understanding the full impact of the psychological consequences of injuries and their management can help young dancers through difficult times, facilitate recovery, and perhaps help avoid injury mismanagement. Toward those ends, this review has two objectives: to present two case studies that describe salient issues that may arise when a young dancer is injured, and to outline practical strategies to help teachers manage psychological recovery in class and rehearsal.The case studies were acquired through in-depth interviews that were conducted by the authors following informed consent. The cases are described through the stories of young dancers.Pseudonyms are used to maintain confidentiality.

Case 1: Emily

Emily,a vivacious 16 year old,experienced difficulty in her right hip when she was 12. She had rushed to an early morning class and started dancing without a warm-up.Initially,she experienced a “clicking” sensation and pain in one hip that eventually progressed to pain in both hips, lumbar spine, and knees.

She did not seek treatment at first, but Emily knew that something was “not right.”Over the course of 6 months she saw a physical therapist,rested when she could, and iced when she had to dance. Emily did not find the therapy helpful, but never sought the opinion of a physician. The physiotherapist diagnosed medial snapping hip syndrome, but Emily “didn’t understand what an injury was.”“It was like, I’m in pain but this is going to go away,”she thought.

She kept dancing and felt that her “whole body was falling apart,” and her dancing was suffering. She said “it drove me crazy!” and described the injury as a major stressor that “made a big impact on my life.” She was “overwhelmed emotionally” and experienced many different negative emotions. She described frustration with her body, and her teachers. She did not understand what was happening to her physically — she did not understand the injury. Emily thought that her teachers did not believe that she was injured, yet she felt neglected in class. She was not provided with feedback, positive or negative. She felt very alone and unsupported by her teachers.Anger filled her once positive carefree spirit and she was not able to perform up to her own standards.She became jealous of her friends and others in her class. Eventually she became depressed, but was “too afraid” to stand up and say that she was in pain and needed support. When she finally did say something, she knew that her teacher was not happy to hear about the injury. She reported that her teachers would say “just do it, you are fine!” They were “authority figures” in Emily’s mind, and so she continued to dance “full out” in pain. She managed the injury herself and cried after every ballet class. At one point, Emily began to engage in self-mutilation, by cutting her arms. She would wear long-sleeved dance wear in classes to hide the cuts. She admitted that she cut her arms to punish herself, but also as a means of expressing and relieving frustration that she could not communicate verbally. At one point she seriously contemplated suicide. She was referred to a psychiatrist to help her unravel the emotional turmoil while she maintained her dance focus and managed the injury herself.

At age fifteen,her new dance teacher referred her to a physician who specialized in dance medicine. She began to understand her injury and how it limited her ability, but not her passion to dance. She learned how to manage her discomfort and that she was not to blame for her injury.She continued to see her psychiatrist weekly and began exploring some of the emotional issues that arose from family discord as well as from her injury.

Emily, at 16, continues to dance. “Some days, I’ll just have an amazing class and it won’t hurt, and then some days I will just stand in fifth, and rotating my leg will kill it right away.”When Emily has a teacher “who is more lenient” and does not force a 180 degree turnout, her hip pain is tolerable. However, a teacher might force her turnout by insisting “I don’t care, I want your leg at 180 degrees, and your fifth position to be a fifth.” When this happens she says her pain and discomfort depend on whether she is allowed to make adjustments to the demands of class herself. She reflects that she dances and moves differently when she is happy, “I figure that when I feel happy and take class it’s very different than when I’m angry and trying so hard to get things right. I’m sure that I’m jamming things, not think- ing about… holding my body to prevent injuries, or I’m sure there are things that slip by me when I’m thinking so much about the negative.”

Emily’s advice to young dancers who suffer an injury is to “stop dancing until the injury has gone and find out everything you can about the injury.” Her advice to teachers is to refrain from offering medical advice about injuries and their management if they are not knowledgeable. She wishes that she would “have been educated… about dance injuries” and prevention of injuries when she was younger.

Case 2: Kristen

Kristen noticed a clicking in her left hip when she was 14 years old. At first, there was no pain associated with the clicking. Several months later she began to experience increasing pain and clicking. Kristen maintained her full-time dance education; however, when she finally consulted a physical therapist she was experiencing pain when she lifted and held her leg in various positions including in flexion and in grand battement.

According to Kristen, the physical therapist told her that she had a tight iliotibial band, as well as weak iliopsoas, gluteus maximus, lateral rotators, and abdominal muscles. An exercise program was designed to strengthen weak muscles and she was referred to an orthopaedic surgeon who diagnosed “shallow acetabulums,”which meant that the head of the femur moved freely in the hip socket. Kristen’s iliopsoas muscle became inflamed and her pain increased. She stopped dancing and exercising and was subsequently given a cortisone injection by her physician.

Kristen was told that she had to stop dancing. This news sent her into a downward emotional spiral. “I lost all my self discipline and ambition,” she explained. “I stopped eating to punish myself because I felt it was all my fault. I was no longer the person I wanted to be — a dancer. I felt like an intruder in a world of which I was no longer a part. The question I asked myself everyday was ‘Who am I when I am no longer a dancer?’”

Kristen experienced numerous negative emotions. She was angry and wondered what she had done to deserve such a blow to her young life. She withdrew from her friends because she was jealous of their ability to dance. She felt depressed and as though she had let everyone down, her family, friends, teachers, and most of all herself. Every day was an uphill emotional struggle. She felt “useless and incompetent” surrounded in a dance environment in which everyone was moving and dancing — everyone but her. She watched her friends do what she longed to do. She felt trapped, frustrated, and extremely uncomfortable and out of place in the dance school — a school that she had loved.

Kristen’s career as a dancer came to a premature and emotional end. Her uphill struggle with injury gave her strength and insight, and helped her to contribute to dance in a different way. Her struggle and new path are revealed in her words: The most important things ever said to us are said by our inner selves. Dance must recognize rehabilitation as a physical and psychological process. The mind becomes just as injured as the body. Who am I now? I am no longer a dancer but a dancer who has the knowledge, understanding and experience of an injury that has taken me through a journey of physical and emotional pain and fortunately with love and support, I came though the other side to find a different path within the same field, dance medicine.

The Psychological Impact of Injury

These cases provide evidence of the potentially serious psychological impact of injury on young dancers and provide insights about injury management. As educators, we have much to learn if we listen to the stories of these two young women. Of course, each dancer is different, but both cases and current research in dance science indicate that there are similarities in responses of all dancers to being injured. For example, in the cases described here, both dancers delayed medical attention and continued to dance through pain and uncertainty about the injury. Most dancers do not seek medical treatment for their injuries [17] and manage injuries themselves.In each of these cases, the dancer had insufficient information about injury and its management, yet attempted to dance and care for the injury herself. Eventually each dancer contacted a physical therapist. Through their struggles with the physical aspect of injury, there were the psychological consequences that were equally, if not more, disruptive and potentially life threatening.

Both Emily and Kristen experienced a range of negative emotions that manifested serious emotional and physical consequences. The emotional upheaval was overwhelming and affected not only their dancing but other aspects of their lives.Some of the emotions were a result of the limitations imposed by the dance injury itself and some were a consequence of the context. Both experienced loneliness, frustration, jealousy, guilt, a sense of isolation,and a lack of support.In both cases,there is evidence of depression and conflict over identity. This is not surprising given the intense focus on dancing, often to the exclusion of other activities,for young dancers in training schools. Brewer [18] found that injured athletes with a strong athletic identity were more prone to depression. For the two dancers we interviewed, dance was an integral part of their lives. When dancing was inter- rupted, their lives seemed to them to be so shattered that both began to engage in harmful behavior.Self-mutilation and anorexia were manifested in these young dancers in order to punish themselves for being injured. These harmful behaviors offered each of them a sense of control and self-expression.

For Emily, dance was an outlet for expression and an activity that gave her a sense of competence and identity. The dance environment also represented security and control in her life in the face of family discord. Once injured, external supports and self-worth were threatened. Her way of coping was to engage in self-punishing behavior. Similarly, Kristen engaged in harmful behavior to “punish” herself. Both girls were fortunate to have social supports that helped them work through their emotional difficulties. Emily was referred to a psychiatrist and Kristen had an extremely supportive and insightful teacher who helped her re-organize her life and thoughts about dancing. Initially, however, both girls engaged in harmful behavior in the absence of professional help or mentoring.

Recommendations for Facilitating Psychological Recovery

Coping with dance injury has physical, psychological, and social dimensions, all of which involve trust. One must first trust one’s own kinesthetic sense that something is wrong — that an injury has occurred — and then consciously acknowledge that injury.Subsequently,treatment is needed and the dancer must trust that the medical practitioner knows how to manage dance injuries. Mainwaring and colleagues [19] demonstrated that most dancers do not seek treatment because they do not trust that medical practitioners are sufficiently knowledgeable about dance injuries or dancers’ lives. However, medical treatment should be the first step in managing dance injuries, especially in adolescents. These dancers, with their special vulnerabilities due to growth spurts, [20] do not have the experience to manage their own in- juries.

The educator has a unique role in preventing and facilitating the management of injuries in young dancers. Educators are important role models and as Emily emphasized, authority figures have inherently powerful positions. Therefore, a teacher can be critical in the acknowledgment of injury,shepherding the dancer to the medical practitioner, and helping the young dancer to trust her own kinesthetic sense and to know her body. It is important to help young dancers understand the difference between pain that signals “harm” versus pain that “hurts” as a result of sore muscles from active training. As one teacher described, “I try to teach the difference between a good hurt and a bad hurt right off the bat.There are too many schools where students are afraid to speak up to get help until it is too late.” [21]

Young dancers can benefit greatly from teachers who help them to respect and look after their bodies. The teacher is trusted by his or her students and has a great amount of power and therefore, responsibility. Dance teachers have an important role to play in injury management.

Second, rest may be a critical component of the healing process. If the dancer does not get sufficient rest, the injury may become worse or develop into a nagging chronic or overuse injury that stays with the dancer for years.However,the dancer will not heed the advice to rest if she does not trust the practitioner and, in turn, the practitioner does not understand the unique context of the dancer. The dancer needs to stay mentally and physically conditioned. Consequently, understanding from teachers,companies,directors,and choreographers is an important part of psychological rehabilitation. There are a number of psychosocial strategies that teachers can suggest to facilitate psychological recovery during and after a period of rest.These are outlined in the section entitled “Psychosocial Strategies.”

Most research on stress and recovery from injury identifies social support as a major contributing factor to healing and coping. [14,22-25]

Adequate social support may be a critical component in helping the young dancer through a difficult phase or facilitating a referral to a mental health worker. As the two cases illustrate, psychological well-being was affected by physical injury. Disordered eating or an eating disorder, in particular, could manifest as a result of dance injury. We already know dancers may be at risk for disordered eating even when injury is not a factor. [26]

For example, female ballet dancers 11 to 17 years of age were found to score higher than non-dancer controls on five subscales of the Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI) [27] : drive for thinness, bulimia, interpersonal distrust, ineffectiveness, and perfectionism. [28]

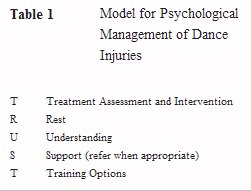

One of the major ways that we can support young injured dancers is to apply a coping model for injury management, introduced here and illustrated in Table 1, and implement training options for the dancers. The following section highlights practical strategies for educators to help young dancers cope with the physical and psychological challenges of injury.

Practical Strategies

Given the information and insights provided by the two dancers, there are several practical strategies that teachers may employ to assist the injured and rehabilitating dancer. Two important issues need to be addressed: the dancer’s internal desperation about being “useless” (or loss of self-esteem) and losing time from dance; and the dancer’s sense of isolation and abandonment from the group. The following suggestions can potentially alleviate the dancer’s fears about loss of time, and the sense of isolation that may arise from being injured as well as provide positive mental strategies to facilitate recovery. Teachers can look at solutions in four areas:

1. Modification of dance activities,

2. Alternative activities during dance practice,

3. Activities outside the studio, and

4. Encouragement of psychosocial strategies for recovery.

The practical strategies have been generated from the first author’s research and training in rehabilitation psychology,and from the second author’s expertise and training in teaching dance for over 25 years. For medical information on “management of injuries in the young dancer” the reader is referred to Luke and Micheli. [29]

Modification of Class Work and Rehearsal

It is important to help the dancer to understand what needs to be modified and why. The more clearly she comprehends how to alter the movement or choreography in order to prevent extending the period of injury, the more active the dancer will be in making these choices. Modifying movement in class can also allow time to re-pattern behaviors that can predispose the dancer to continued injury. The teacher can also assist the dancer in developing an approach to class and rehearsal that modifies material, but still allows the dancer to feel as if she is working and progressing. In other words, it is important to give the dancer tasks to work on, and not just tell her what to avoid!

The dancer needs to be given verbal support and correction in class and rehearsal. It is crucial not to ignore the dancer because she is injured and may be modifying movements or sequences.An invisible dancer, whether injured or not, is a dancer who can suffer loss of self-confidence and identity. [18]

Injured dancers also need to feel that they have some control over the situation. The director can give the injured dancer the prerogative of not running a piece and letting an understudy step in, while still reassuring the dancer that the part will not be withdrawn completely, and once she is able to dance fully, she will be reinstated. Research shows that an individual’s positive well-being and health are associated with having a sense of per- ceived control. [30]

Alternative Activities If the Dancer is Unable to Participate

Sometimes an injury is of such severity that the dancer cannot physically participate in class or rehearsal to any extent. In this instance, whenever it is possible,instructors should let the dancer assist in class by giving specified corrections to students. It is probably better to select a different level than the one the dancer usually takes, to avoid resentment or disapproval on the part of peers. The dancer can also coach lower level students in time outside class, and it is helpful to give the dancer specific tasks to work on with these students. If time permits, the teacher can meet with the dancer to discuss pedagogical issues and help her develop strategies for working with and coaching other dancers.

The director can allow the dancer to assist in rehearsals by taking notes in run-throughs,coaching certain dancers while the choreographer is working on another group, making notes on new material, and letting her observe and give notes on a run that the choreographer cannot attend. It is important that the other dancers understand that the choreographer or director is giving this authority to the assistant, so that appropriate attention and respect is given. It is also important to be clear with the other dancers that replacing the injured dancer is a temporary situation, and when recovered, the dancer will return to parts in repertory. As with any group dynamic, communication is a key element to understanding and good rapport.

The issue of whether or not the injured dancer should sit and observe classes and rehearsals is a complex one. Having the dancer watch class can sometimes be more detrimental than useful, depending on the dancer. The teacher must always consider whether the negative effects of loss and helplessness are greater than the educational benefits. Three or four days of observing might prove beneficial, but weeks or even months of sitting passively on the side can be devastating and depressing. Recall that both Emily and Kristen were jealous of their friends who were dancing. If the dancer is assisting in other classes and rehearsals, she may feel like she is still involved and making a contribution rather than feel uncomfortable and excluded from class. The regular class time might be an appropriate time for physical therapy sessions or personal work. Again, open communication can assist the teacher in knowing the unique needs of each dancer.

Outside the Studio

The teacher can suggest social activities such as field trips,get-togethers,or film showings,that the dancer can do with the peer group, as well as encouraging the dancer to spend time with a social group of non-dancers. Giving the dancer reading and viewing of dance materials can sustain the dancer’s interest and progress. Some dancers love to read about their own particular injury. Mainwaring [9] found that injured athletes wanted information about their injury and the associated rehabilitation process. Furthermore, there is ample evidence that patients have a high desire for information. [31,32]

In our case example, Emily mentioned that she wished that she had been educated about dance injuries when she was younger. Teachers can suggest that injured dancers ask their medical practitioner for information on their injury and the rehabilitation process. Also, students may be encouraged to read about anatomy so that they are knowledgeable about their bodies. For example, Robson states that: Many schools are including stretch and strength programs, aerobics programs, lectures and workshops on anatomy, and how to care for minor injuries and injury prevention in their curricula, not only at the college level but in high schools as well. It is vitally important that current research in performing arts medicine be included in these programs, as the students who participate today will be the teachers of tomorrow. [33]

It is important for the teacher to work with medical personnel and also to develop a local referral list of individuals who are reliable and knowledgeable. It is helpful to think of all of these interested parties as a support team, and encourage discussion of the dancer’s treatment and progress with the medical personnel, the parents, other concerned teachers, as well as with the dancer. A referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist may be in order when a dancer is having difficulty coping. In such a case, the physician may be in the best position to do this, but there may be times when a teacher might be asked for his or her opinion. In some schools, (e.g., the National Ballet School of Canada) health professionals, including psychiatrists, are available to the students. [34]

Ultimately, everyone involved must be vigilant about ensuring that rehabilitation is considered in a serious manner. Furthermore, it is important for young dancers to recognize that supportive health professionals, including psychologists and psychiatrists, are available. Complete physical, psychological, and social rehabilitation extends beyond physical healing and teachers can play a vital role in monitoring, supervising, and supporting both physical and psychological recovery from injury.

Psychosocial Strategies

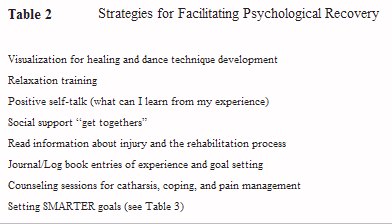

The teacher can facilitate recovery by encouraging the use of psychosocial strategies. Table 2 identifies techniques that teachers may want to suggest to the dancer. These techniques are taken from clinical, rehabilitation, and sport psychology. Visualization, or imagery, can be used to work on dance technique while the dancer refrains from activity during injury. In this way, neuromuscular stimulation is provided in the absence of activity. [35-41]

Relaxation training is also useful for dancers; the rehabilitation period may provide a good opportunity to learn relaxation skills that can, in turn, be used in many situations, not just those that involve recovery from injury (e.g.,calming performance anxiety). The best way to learn these skills is for the teacher to consult with a trained psychologist or mental skills practitioner. Alternatively, teachers may want to recommend or use the available source books on the use of imagery in dance. [42,43]

In addition, teachers can encourage positive self-talk by suggesting that dancers listen to the voice within and ensure that negative comments are transformed into more positive ones. Another strategy is for the teacher to foster confidence and a sense of belonging for the injured dancer by organizing social interactions that include the dancer. This will help the dancer feel that she is still part of the ensemble.

Finally, the dancer, teacher, and director need to establish realistic goals for return to full activity in discussion with medical personnel, teachers, and parents. It may energize the dancer initially to be given information that she will be dancing very soon, but if this is false hope, the resulting let down is not worth that initial boost. It is commonly accepted in sport psychology that goals need to be “SMARTER” (i.e., specific, measurable, attainable/acceptable, realistic, timebased, evaluated, and recorded). Table 3 presents a rehabilitation goal sheet (adapted from Gordon and associates [44]) that illustrates the kinds of questions that need to be posed in order to set appropriate rehabilitation goals.The dancer and teacher may want to complete the sheet together. In doing so, realistic expectations can be met by both parties. The dancer needs to be positive and hopeful, but also needs to understand the severity of the injury and the reality of the time needed to heal and rehabilitate. Teachers can be critical figures in helping young dancers manage their injuries physically and psychologically and assisting them to create a lifetime of healthy dancing.

Summary

The two case studies describe the psychological impact of long-term injuries.These examples highlight the emotional distress and maladaptive behaviors found in injured dancers. Practical strategies for helping young dancers cope with the psychological aspects of injury are provided.While more research is needed in the physical, psychological, and social consequences of dance injuries, it is clear that teachers play a significant role in guiding dancers to a healthy outcome.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michael Gadon and the editors of the journal for commenting on an earlier version of this article.

The Authors

Lynda Mainwaring, Ph.D., C.Psych., is a member of the Faculty of Physical Education and Health at the University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Donna Krasnow, M.S., is an Associate Professor of Dance, in the Centre for Fine Arts,York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Lauren Young is the assistant manager and aerobics coordinator for Womenzone Health Club, Watford, Hertfordshire, England.

Correspondence: Lynda Mainwaring, Ph.D., C.Psych.,Faculty of Physical Education and Health, University of Toronto, 55 Harbord Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5S 2W6.

References

1. Sammarco GJ: The dancer’s hip. Clin Sports Med 2:485-498, 1983.

2. Stone D: Hip problems in dancers. J Dance Med Sci 5(1):7-10, 2001.

3. Poggini L, Losasso S, Iannone S: Injuries during the dancer’s growth spurt:Etiology,prevention,and treatment. J Dance Med Sci 3(2):73-79, 1991.

4. Gordon S: Sport psychology and the injured athlete: A cognitive-behavioural approach to injury response and injury rehabilitation. Sci Period on Res and Tech in Sport, March, 1986, pages, 1-10.

5. Nideffer RM: Psychological aspects of sports injuries: Issues in prevention and treatment. Presented at the Seventh World Congress of the International Society of Sport Psychology, Singapore,August, 1989.

6. Rotella RJ, Heyman SR: Stress, injury, and the psychological rehabilitation of athletes. In: Williams JM (ed): Applied Sport Psychology: Personal Growth To Peak Performance. Palo Alto CA: Mayfield, 1986, pp. 343-360,

7. Eaton D:A study of the emotional responses and coping strategies of male and female athletes with moderate and severe injuries. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Western Michigan University, 1996.

8. Leddy MH, Lambert MJ, Ogles BM: Psychological consequences of athletic injury among high-level competitors. Res Quart Exer Sport 65(4):347-354, 1994.

9. Mainwaring L: Restoration of self: A model for the psychological response of athletes to severe knee injuries. Can J Rehab 12(3):145-156, 1999.

10. May J, Sieb G. Athletic injuries: Psychosocial factors in the onset, sequelae, rehabilitation and prevention. In: May JR, Asken MJ (eds): Sport Psychology: The Psychological Health of the Athlete. New York: PMA Publishing, 1987, pp. 157-185.

11. Rose J, Jevne R: Psychosocial processes associated with athletic injuries. Sport Psych 7:309-328, 1993.

12. Smith A, Scott S, O’Fallon M, Young M: Emotional responses of athletes to injury. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 65:38-50, 1990.

13. Wiese-Bjornstal DM,Smith AM,Schaffer SM,Morrey MA: An integrated model of response to sport injury: Psychological and sociological dynamics.J Appl Sport Psych 10(1):46-69, 1998.

14. Brewer B, Linder D, Phelps C: Situational correlates of emotional adjustment to athletic injury.Clin J Sport Medicine 5:241-245, 1995.

15. Smith R, Smoll F, Ptacek J: Conjunctive moderator variables in vulnerability and resiliency research:Life stress, social support and coping skills, and adolescent sport injuries. J Pers Soc Psych 58(2):360-370, 1990.

16. Brewer B: Emotional adjustment to sport injury. In: Crossman J (ed): Coping with Sports Injuries: Psychological Strategies for Rehabilitation. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 1-19.

17. Krasnow D, Kerr G, Mainwaring L: Psychology of dealing with the injured dancer. Med Probl Perform Art 9:7-9, 1994.

18. Brewer BW: Self-identity and specific vulnerability to depressed mood. J Personality 61:343-364, 1993.

19. Mainwaring L,Kerr G,Krasnow D:Psychological correlates of dance injuries. Med Probl Perform Art 8:36, 1993.

20. The Education Committee of the International Association for Dance Medicine and Science:The challenge of the adolescent dancer. J Dance Med Sci 5(3):94-95, 2001.

21. Neville R: Personal communication, November 2001.

22. Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Pierce GR: Social Support: An Interactional View. New York: Wiley, 1990.

23. Wasley D, Lox CL: Self-esteem and coping responses of athletes with acute versus chronic injuries. Percept Motor Skills 86:1402, 1998.

24. Wiese-Bjornstal K,Smith A:Counseling strategies for enhanced recovery of injured athletes within a team approach. In: Pargaman D (ed): Psychological Bases of Sport Injuries. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology, 1993, pp. 149-182.

25. Williams J, Rotella R, Heyman S: Stress, injury, and the psychological rehabilitation of athletes. In: Williams J (ed): Applied Sport Psychology: Personal Growth to Peak Performance. Palo Alto, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company, 1986, pp. 409-428.

26. Garner DM, Garfinkel PE: Sociocultural factors in the development of anorexia nervosa. Lancet 2:674, 1978.

27. Garner DM,Olmstead MP,Polivy J:Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Intl J Eat Disorders 2:15-34, 1983.

28. Neumarker KJ,Bettle N,Neumarker U,Bettle O:Age and gender-related psychological characteristics of adolescent ballet dancers. Psychopath 33(3):137-142, 2000.

29. Luke A, Micheli LJ: Management of injuries in the young dancer. J Dance Med Sci 4(1):6-15, 2000.

30. Sheeran P, Conner M, Norman P: Can the theory of planned behavior explain patterns of health behavior change? Health Psych 20(1):12-19, 2001.

31. Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Irvine J: What role do patients wish to play in treatment decision-making.Arch Internal Med 156(13):1414-1420, 1996.

32. Strull WM, Lo B, Charles G: Do patients want to participate in medical decision-making? JAMA 252:29902994, 1984.

33. Robson B:Disordered eating in high school dance students some practical considerations.J Dance Med Sci 6(1):7-13, 2002.

34. Greben SE: Career transitions in professional dancers. J Dance Med Sci 6(1):14-19, 2002.

35. Batson G: Dancing fully, safely, and expressively:The role of the body therapies in dance training. JOPHERD 61(9):28-31, 1990.

36. Batson G: Conscious use of the human body in move- ment: The peripheral neuroanatomic basis of the Alexander Technique.Med Probl Perform Art 11(1):3-11, 1996.

37. Dowd I: Taking Root to Fly (2nd ed). North Hampton, MA: Contact Collaborations, Inc., 1990. 38. Eddy M: An overview of the science and somatics of dance. Kinesiology and Medicine for Dance 14(1):20-27, 1991.

39. Krasnow DH, Chatfield SJ, Barr S, Jensen JL, Dufek JS: Imagery and conditioning practices for dancers. Dance Res J 29(1):43-64, 1997.

40. Matt P: The nature of Ideokinesis and its value for dancers. In: Fitt SS (ed): Dance Kinesiology (2nd ed). New York: Schirmer Books, 1996, pp. 335-341.

41. Sweigard LE: Human Movement Potential: Its Ideokinetic Facilitation. New York:Harper and Row,1974.

42. Franklin E: Dance Imagery for Technique and Performance. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc., 1996.

43. Franklin E: Dynamic Alignment Through Imagery. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc., 1996.

44. Gordon S, Potter M, Hamer P: The role of the physiotherapist and sport therapist. In: Crossman J (ed): Coping with Sports Injuries: Psychological Strategies for Rehabilitation.New York:Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 1-19.

Copyright © 2003 J. Michael Ryan Publishing, Inc. All rights reserved. Subscriptions: J. Michael Ryan Publishing, Inc., 24 Crescent Drive North, Andover, New Jersey 07821-4000; Telephone: 973-786-7777; Facsimile: 973-786-7776; Web: www.jmichaelryan.com.